Feature Story:

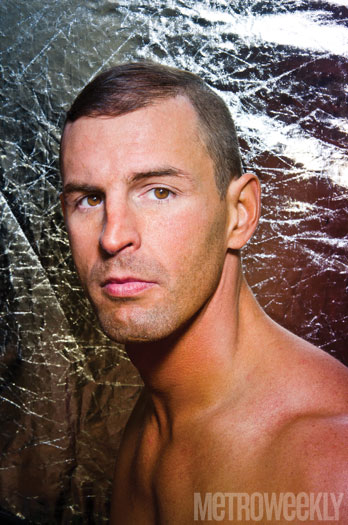

Center stage is quite possibly the last place you'll find Chris Svoboda. While she's had a hand in multiple efforts over the years, she's made sure not to be the face of any of them. Her activism has been on the quiet side.

"I have a family member that said, 'Why are you such a flag-waver?'" Svoboda says with a laugh. "I'm thinking, 'I am not a flag-waver at all, honey. You have not seen a flag-waver.'"

![Chris Svoboda]()

Chris Svoboda

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Still, the 51-year-old Svoboda, born in D.C., raised in Richmond, and still dividing her time between the two, is deeply involved. She points to her Catholic upbringing, though not identifying as Catholic herself, for her benevolent values. Her parents, who actually met on Capitol Hill where her father helped to support his medical studies by working as an elevator operator and her mother worked for Connecticut's Sen. Thomas Dodd, raised her to value service to others.

"It's giving back," she says. "That was the lesson taught to me in life: You were given so much that you need to give back."

One very recent expression of that is her work on a short film, Russia Declares Discrimination Newest Olympic Sport, a challenge to all nations with anti-LGBT laws. Since its early February debut, it's racked up nearly a million views. She's also a co-chair for the Mautner Project's annual gala, this Saturday, March 8. Activism like that makes it hard to stay in the shadows.

Sitting in her D.C. home, her cat Simba nearby, as well as several musical instruments, Svoboda seems comfortable opening up about her story. She's somewhat guarded about a few topics, but graciously so. Pulling back the curtain to offer a peek behind the scenes doesn't even make her wince. So take a look, because there's a lot happening.

METRO WEEKLY: I know so little about your background. Let's start with what you studied.

CHRIS SVOBODA: My undergraduate degree was a mathematics/computer-science major. Later, I went to Rutgers for law school, contracts. I've been a technology and science geek from a very young age. I was into computers when I was in high school, the late '70s.

MW: You must have a favorite Star Trek character.

SVOBODA: Hmm. No. You'd think I'd be into that. And Dungeons & Dragons.

MW: You got the science, but not the nerdy?

SVOBODA: I got the other nerdy stuff. Building computers and soldering things. Both my grandfather and my father worked with their hands and I learned how to repair things. When I'd break a window with a baseball growing up, it was a life lesson. [Laughs.] My dad would teach us how to change the pane in the window, how to do the points and all the stuff you need to do. We'd get in trouble, but we'd be taught the lesson on how to fix something. So my brother, my sister, myself, we can change tires and do plumbing repairs. We can do all sorts of stuff.

MW: While your father was practicing medicine, what did your mother do in Richmond?

SVOBODA: Interior decorating. She was also very involved in volunteerism. It was always about giving back. I grew up in a Catholic family, church every Sunday. Later in life, my dad started to go to church every morning, Mass seven days a week. It was always a life of service.

My mother had the little social groups that she belonged to, but they were all involved in service projects. We would go along with mom when she would go to the Virginia Home, which was a public facility for people with paralysis, quadriplegics, people with debilitating diseases and whatnot. We learned at a very early age the importance of being involved and how everything that you did could change and touch a life. It was a behind-the-scenes thing. I think that's why I've always been very comfortable not being in the limelight. That, coupled with living a life -- 50 percent of my life was pretty much lived in the closet.

MW: And "pride" is a sin.

SVOBODA: The way I was raised, it wasn't to be a "boastful" life. It was to be a life of service. You did things behind the scenes and you didn't call attention to yourself. I was also taught to stand up for what you believe in.

MW: You said you were closeted. Do identify as a lesbian? Queer? Bisexual?

SVOBODA: I identify as a gay man trapped in a lesbian's body. [Laughs.] I am the lesbian Martha Stewart. All my gay guy and straight women friends want me to come over to fix stuff. I don't know how to explain it. I'm probably one of the few lesbians who knows "passementerie."

MW: Passementerie?

SVOBODA: Oh, my God. Are you really a gay guy? Passementerie is all the fringe and the trimmings on your curtains. All the tassels, the silk-woven tape, all that. I got that from my mom. I love interior design. I love decorating with flowers. I love crafts.

MW: Did you have a sort of coming out?

SVOBODA: Yeah, it was called a debutante ball! We grew up in a world where it was a derogatory thing. Luckily, you could be hidden and no one would know. I was very social, but it wasn't the social life I wanted to have. I grew up in a heterosexual world and I wanted to fit in. When I left, I was able to live my life -- but I still had a foot at home. It took a long time to reconcile that.

![Chris Svoboda]()

Chris Svoboda

(Photo by Todd Franson)

MW: But when did you become self-aware of your sexual orientation? Some people know at 5, some at 35.

SVOBODA: It was something that you didn't really know what it was. Yeah, you had a crush on that teacher or that friend or whatever, but there wasn't anything out there to relate to. And there was no one you could talk to about it. That didn't exist.

What there was, there were dance clubs. The guys -- at this point I didn't know they were gay guys -- we all liked to hang out, all liked to go dancing. We'd go to the "bad" section of town. I don't remember where we told our parents we were going, but we ended up at these nightclubs. They had drag shows and it was so much fun. We had a blast.

MW: Where did you go after high school? Where did you get that math/computer-science degree?

SVOBODA: I went to Sweet Briar. That was a wonderful, wonderful place. I had the dearest friends from both high school and college. My professors from both high school and college are in my life. I've lived a very blessed life with the people and opportunities that have been presented to me.

I did a sort of minor study in studio art. I wanted to go into architecture. I'd always done work on the stage, lighting and sound systems. I created a computer program that would trigger lights and sound.

But then everything exploded in my life. The day after I graduated, my dad had a seizure and they found two brain tumors. Everything was put on hold. I stayed in Richmond and helped my mom take care of him until we figured out what was going on. Then I went off to work in the film business, a year later.

MW: In L.A.?

SVOBODA: No, in North Carolina. Dino De Laurentiis had some film studios down there.

MW: Did you have connections from school?

SVOBODA: No, I just wrote a letter that elicited a response within about three days from the studio manager. She set up some interviews for me. [Laughs.] I can't even remember what I wrote. I had a couple interviews and got a job. I packed some stuff, took my dog and went down there and worked on a bunch of different projects.

We had a summer home down there and I had a place to stay. It was a good place to go that allowed me to just figure out what I wanted to do. And in the film business there are just so many aspects of it. It was the behind-the-scenes financing, the putting things together; and the creative stuff of the writing and the acting. In school, at summer camp, I'd done theater so I enjoyed all that stuff. All the different pieces of my life could come together. I had a nice opportunity down there to work on a bunch of different projects and sort of get away.

After a couple years down there, I met a French producer. He was working on a project and was going to hire a bunch of American actors, and he wanted a liaison. He hired me to be associate producer and I moved to Paris. I lived there and we shot the film in Madrid. I was there for about a year.

MW: What was the film?

SVOBODA: It was only released in Europe. I don't even remember what it ended up being called over there. But I came back here, moved to L.A. and was there for about 16 years.

MW: Was there an opportunity waiting for you in L.A.?

SVOBODA: No, but I had a friend who was willing to drive cross-country with me, and I had a number of friends I'd made in North Carolina who were L.A. natives, so I had places to stay. I actually got my first job within the first week, because I was sitting in a hot tub at a party and somebody said, "Hey, if anybody knows somebody, we're looking for somebody to help us with distribution on some of our little movies." And I went to work for Direct Cinema Limited, which was distributing all the tiny, cute films this guy named John Lasseter was making with his little animated company called Pixar.

MW: The hats you've worn just in the film industry --

SVOBODA: -- are insanely crazy, yep.

MW: You must have good celebrity stories.

SVOBODA: Not really, no. I'd rather stay away from celebrity stuff. I've worked with a lot of really fun, interesting, amazing people. But they're just people.

MW: Do you miss L.A.?

SVOBODA: To a certain extent. I've made some really fantastic friends out there, but it's really messed up a lot of people. People who were wonderful going into it, and then as fame and fortune came into their lives.... I had some dear friends who are still dear friends, and some dear friends who just completely changed.

![Chris Svoboda]()

Chris Svoboda

(Photo by Todd Franson)

MW: Moving around, when did you start to develop your own sense of the gay community?

SVOBODA: That wasn't until L.A. Finally, I got involved. With friends, we'd volunteer for the AIDS Ride. I got involved with The [Gay and Lesbian] Center.

I was on the board of ALSO, the Alternative Lifestyle Scholarship Organization. I don't think it exists anymore. Some guy's family had cut him off, stopped paying his college tuition when they found out he was gay. Twenty years later, he had some money and started this organization. We would pay out -- not big grants -- a thousand dollars, $2,500, to gay students whose parents had cut them off when they found out they were gay. That helped expand my community and my exposure.

MW: So, no big epiphany? No running out into the street shouting, "I'm a lesbian!"

SVOBODA: No, no, no. I finally just got to a place where I started feeling it was okay to be me.

I was able to get involved with GLAAD out there. And HRC. There was another organization I was on the board of called Hollywood Helps. It was an organization that had representatives from all the different studios, production entities, the Chamber of Commerce, and we raised money. This was a behind-the-scenes organization to help people in the industry living with AIDS, people who were having financial troubles, whether it was their insurance wasn't covering the cocktail or they couldn't make the car payment or they used their money for meds and didn't have money for food. I was the treasurer. The coolest thing was, every month, being like Santa Claus. I got to write them checks, directly, for whatever their request was. I can't remember what the maximum was, but it was like $850 for a mortgage payment or whatever was needed to tide them over. It was just the greatest thing to be able to do that.

MW: The AIDS epidemic really pushed the direction of your activism?

SVOBODA: It did. I had friends who.... [Tears up.] It was that time.

MW: I'm sorry to upset you.

SVOBODA: You read the reports, the stories of the history of what slowed down the research advances, the stuff between American scientists and French scientists, and the government, and then you get religion into it -- and there are lives at stake. And to a certain extent, once they identified transmission, then you get upset with people who don't change their habits. That's one of the things that really upsets me so much with kids today, with youth who think they're immune and aren't practicing safe sex and they aren't educating themselves. They're pretending it's something that's not going to get them. They're being foolish. We have discussions about that, us adults.

MW: This must come up at the Richmond Organization for Sexual Minority Youth.

SVOBODA: It does. And the kids are amazing there, because we really do give them a sense of family, a safe place. ROSMY is a wonderful, wonderful organization. We have a 24-hour "911 service" for kids, pre-cleared foster homes for kids who might get thrown out or locked out in the middle of the night by parents. They call our 911 and they have a place to go immediately.

MW: On a different Richmond note, hadn't you told me you were working on a restaurant there with your brother?

SVOBODA: No, my brother and I have invested in a brewery that's going to open in Silver Spring. It's two married lesbians, and the brother-in-law of one has moved here from Denver to be the brewmaster. They're building it now on East-West Highway. Hopefully, they'll be opening by the end of May.

The restaurant I'm working on is actually with my first boyfriend. In seventh grade, David was my boyfriend. David is gay. He was the executive [sous] chef at the Inn at Little Washington. He's one of the most creative chefs, ever. And I'm a foodie. I'm a gourmand and foodie, two different things. I love sort of the highbrow stuff, but I also love the creative genius. I really enjoyed Minibar when it was the six or eight seats. Because I'm a geek! I love the science. I have all the stuff to do that, all the agar agar, all the different chemicals.MW: How do you feel about foam?

SVOBODA: Hello! I've got my foam guns up there. [Points to a cabinet.] I've got both the carbon dioxide and the nitrous oxide to make the different whipped creams and foams.

MW: How much time do you spend in D.C. versus Richmond?

SVOBODA: It all depends on the projects. When I'm working on the restaurant with David, I'll be in Richmond for most of the next three months. If something pops up in D.C., I'll be here.

MW: There's no day job, per se? Just projects?

SVOBODA: Right. I turned 50 a year ago. I had been doing a lot of stuff. A lot of my life had been doing stuff for others, being there for family. I hit 50 and it was the epiphany of it was time for me to figure out what I am going to do with my life, separate from everyone else's lives. So last year I just started doing things that mattered to me, that I wanted to do.

MW: Looking at the video you made recently with Michael Rohrbaugh, is that something you would've done five years ago?

SVOBODA: I would not have had the luxury of the time to be able to drop everything. It was just me and Michael, for the most part, pulling that thing together. The week before shooting, it was just me and Michael trying to raise the rest of the money and get the equipment we needed. I dropped everything and got on the phone and started re-connecting with folks I hadn't spoken to in eons out in L.A. Little by little, everybody was like, "I don't have that piece of equipment, but so-and-so owes me a favor so call them and use my name." Within that one week, we raised the money -- well, not all the money, we're still raising money.

![Chris Svoboda]()

Chris Svoboda

(Photo by Todd Franson)

MW: What are all the steps involved? We all see the finished product, but few of us see how things like this come together.

SVOBODA: I got a Facebook IM from one of my best buddies who said, "Hey, my friend Michael is doing this thing and needs help, and I know that you used to do this kind of stuff." That was Thursday, one week before the shoot. I'd never met Michael, and he was in L.A. We got on the phone later that night and talked for two hours about the idea. I asked him to send me what he had on a budget, what he had on a breakdown of concept, what he had set up as far as crew and equipment, and what he needed, what was missing. After I got off the phone with him I shot out, I don't know, 40 emails. I spent the rest of that night doing emails, phone calls, Facebook, trying to find the people that I needed to put into place. We hit the ground running on Friday morning.

MW: How did Michael sell you on it? Why did you want to be involved?

SVOBODA: Last summer, I had been invited by some friends of mine who have really dedicated their lives to LGBT rights, nationally and internationally, to be a co-host for a function.

MW: Is this an organization? Is there a name?

SVOBODA: It's a group of concerned people working behind the scenes, but this whole thing happened sort of off the record. It was a truly behind-the-scenes event, so I can't give you any particulars. But at that point, a lot of stuff was happening on the international scene, not just Russia. LGBT violence was escalating and these laws were coming into play, while we were in the midst of all this stuff with the Supreme Court here. I heard the reality of what was happening from the victims. When you hear it firsthand, it's even more real than when it's in print, in the news.

I have always felt that we have to speak for those who do not have the ability to speak for themselves, to tell the stories of those who can't tell their own stories. This was an opportunity, working with Michael on this project, to do that.

MW: When was that first phone call?

SVOBODA: When were the Olympics? We posted the video the Thursday before the opening ceremonies, shot it the Friday before. Basically, we didn't sleep for a couple weeks. I'm serious. We had to have it posted before the Olympics, so everything had to be done.

We would've liked to have had another editor, a second set of eyes, but we couldn't afford to hire another editor and we couldn't find one who'd do it for free. So Michael and I sat on the phone going back and forth, little by little, because we started with something that was about four-and-a-half minutes and we knew that we had to have it under two. Michael and I were on the phone going, "Okay, 1:06 to 1:08 can be cut out." We literally went through like that for hours.

Then we needed to work on the music. He wasn't happy with the music, and I'd messed around with songs in college and I had a friend who'd messed around and we were on the phone humming things back and forth. We were writing music and lyrics that Sunday night, trying to get it together. Then, at the 11th hour, King Avriel gave us that song. Gave it to us. We didn't have to pay anything, because she's supportive of what we were doing. We had reached out to music supervisors we knew, friends of friends, but we knew that if we didn't get that, we had to have something. Everybody jumped on board to do whatever they could do.

MW: Another piece of your activism, another example of putting things together, is serving as co-chair of this year's Mautner gala. What's your history with Mautner?

SVOBODA: I was introduced to Mautner about a year and a half ago by some friends who were on the board. I'd had a conversation with them at one of their fundraising cocktail parties. I asked someone on the board, "Why aren't the men more involved?" And it was, like, because they're doing their own thing. I know Mautner had the "Men of Mautner," the one event a year. I said, "Why don't we do that more often?" So they tasked me. I pulled in my "gay husband," Hudson, tapped him to help me coordinate Men of Mautner. We've had a couple dinners to try to get the guys more involved. He's co-hosting the Mautner gala with me, Deb Dubois and Linda Spooner.

That's sort of how I ended up with Mautner. And working with HRC for years. HRC has always been, to me, a very insular organization. I want to see it integrated more than insular. We did a thing about a year and a half ago to get the women of HRC and women of Mautner together to do a happy hour. It was great, because it wasn't just the women -- the guys came. That's where we ended up getting the Friday night comedy night. It's going to be a joint HRC-Mautner event. What's even more exciting is that Lambda Legal is sponsoring. To me, Lambda Legal is really the one that's the unsung hero in all our fights over the last 40 years. They're the ones filing the lawsuits and carrying the lawsuits through. HRC does this great job of lobbying and they've got the membership. Lambda Legal isn't a membership organization. They're more my mentality of behind the scenes. But, man, the work that they're doing is insanely awesome. Lambda Legal is the unsung hero in so much of our battle.

MW: What else might you be working on?

SVOBODA: I'm one of the founding board members of the Virginia Equality Bar Association. We just started that in October.

And almost 20 years ago I was one of the founding board members of an organization called Colors United. It was comprised of students, mostly African-American and Latino, Bloods and Crips. It was an afterschool program to keep the kids off the streets and to help socialize the two opposing gangs. There was a documentary about 15 years ago all about the kids and the program that was nominated for an Academy Award. They want to do another documentary about themselves and where they are 20 years later. Michael and I had actually talked about that. I just got a Facebook IM from a couple of them. I said, "What interesting timing, because Michael and I started talking about that a couple weeks ago."

MW: Seems you're not just plugged into a network, but into the universe. SVOBODA: It's being open, I guess. Being in the moment, being in the now. This moment right now is all we have.

MW: With turning 50 giving you a sort of new drive, where do you want that momentum to take you? Where do you want it to take others?

SVOBODA: I want a world that's fair. I want people to work toward change, toward change that makes the world fair. I think Heather [Mizeur] is working towards that. I've been volunteering on her campaign, since the beginning. She is, to me, what a politician should be. She's all about fairness. She's absolutely awesome.

I think Michael and I, with the stuff we want to do, we want it to be powerful and thought-provoking content. Michael and I were talking about climate change. We were talking about homelessness and hunger. There are so many issues. Michael and I are very excited going forward.

I feel a lot more settled now. I'm comfortable in my life. I'm still frenetic, but it's controlled freneticism. I've learned patience. That was a big thing. I used to be very impatient. Now I'm an extremely patient person. I'm in a really good place.

The Mautner Project Gala & Dance is Saturday, March 8, from 6 p.m to midnight, at the JW Marriott, 1331 Pennsylvania Ave. NW. For tickets, $250, visit whitman-walker.org/mautnerprojectgala.

Ladies & Laughter, benefiting the Mautner Project and the Human Rights Campaign, is Friday, March 7, at 7 p.m., at Artisphere, 1101 Wilson Blvd., Arlington. For tickets, $75, visit whitman-walker.org/comedynight.

...

more