Jeffrey Johnson has been part of Washington's cultural fabric for 15 years, even if he got his start on the stages of Columbia, S.C. But his artistic forays are not limited to the nation's capital. His famous portrayal of Jackie Kennedy Onassis's eccentric cousin Edith ''Little Edie'' Bouvier Beale is legendary, and he's taken his interpretation – some might go so far as to say unnerving re-creation – of her very brief cabaret act beyond D.C. to San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York.

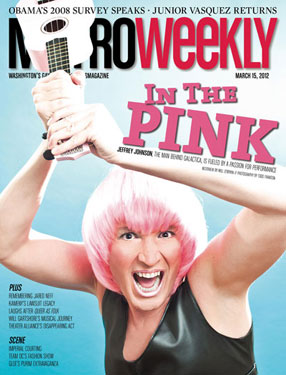

Here at home, it's likelier to be his character Special Agent Galactica, a pink-wigged chanteuse with hints of Barbarella and Las Vegas. Washington is also where he did time as the director of the now-closed Ganymede Arts, a dedicated LGBT theater company.

Jeffrey Johnson: Galactica

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Long before any of that, there was a little boy in the even smaller town of Horseheads, N.Y., nestled into a valley along the Pennsylvania border.

''I did a play,'' recalls the 44-year-old Johnson. ''I was the only fifth grader to be in the sixth-grade play.'' He doesn't remember the title, but does recall he played the part of Shakespeare, decked out in one of his mother's frilly blouses.

''Because I was in that, I knew that I wanted to do it. From childhood, I always knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to perform. I always had dreams of it.''

He guesses he's known he was gay just about as long, though he didn't come out till he was long gone from Horseheads. But it's not as if he had time for a social life. Instead, Johnson's was a childhood primed for the pool, with nearly every free hour dedicated to making him a world-class swimmer – possibly an Olympian.

Today, a world away from Horseheads and the fifth grade, Johnson sits in his Logan Circle-area apartment. His 14-year-old dachshund, Cletus, is at his side. Johnson has just returned from a Saturday-afternoon workshop.

''A friend of mine has her own studios out in Bethesda. She has a bunch of high school- and middle school-aged voice students. She's found that a lot of them want to always work on auditions, get to know how to audition for things. She's spent a lot of time in her classes teaching stuff like that instead of really focusing on voice, so she's starting these 'how to audition' workshops.''

Whatever the audition, it's a pretty good bet Jeffrey Johnson can teach them a thing or two.

METRO WEEKLY: As with the workshop today, what advice would you have for a young person considering a show-businesses career?

JEFFREY JOHNSON: It's not so much that there's a specific thing to say. There's not a catchall. You relay the fact that there are many upsides to doing it, and downsides. You have to be your own biggest fan, because sometimes you're going to find that no one gives a damn. You hit highs and you hit lows. You can't really get into it expecting you're going to make a lot of money, that you're going to be the next Brad Pitt. It has to be a passion. You have to get more out of it than money.

MW: You simultaneously need to have a strong ego and no ego. Would you say that you have --

JOHNSON: An ego?

MW: Passion.

JOHNSON: Most definitely. I don't make money off it, that's for sure. [Laughs.] It's a passion. I don't know what else I could do.

MW: Olympic swimmer?

JOHNSON: I tried that. I never got there. The passion just never carried me through. The passion didn't outweigh the bullshit, basically, for me to say, ''Yes, I can deal with this, because this is what I really want.'' I didn't really want it. It was just something that I naturally fell into as a kid and excelled at.

MW: When you were that kid, the teenage small-town swimmer, where would you go to get into trouble?

JOHNSON: To tell you the truth, I never had that experience. I was at swim practice. I didn't have a childhood, really. From 7 all the way through high school was: Get up in the morning at 5. Go to swim practice. Go to school. Go to ''dry-land workout,'' either aerobics or weight training. Go to swim practice again. Go home, eat dinner, do homework and go to bed. And start all over the next day. Weekends were swim meets. That was my childhood.

MW: Sounds a little Spartan.

JOHNSON: It was full of experiences, but not full of childhood experiences. The very first year I jumped in a pool, I qualified for the state swim team. They knew right off the bat, ''Okay, he's a natural.'' So my parents were very focused on getting me every opportunity in that realm. For the longest time, I was all about it. It felt good to excel. But then I would come home and see all the kids out on the street, playing, all of that, and never really took part in that.

MW: Were your parents more like your coaches, or were they just being supportive of what you wanted to do?

JOHNSON: My dad was excellent in sports as a kid. He could've been a professional golfer, basketball player, baseball player -- he was that good. Never had any support from his folks. Never came to any of his games or matches. Basically, they were so against him doing anything extracurricular that my grandfather would drive past my dad walking home at night from school, as he would come home from work, and wouldn't pick him up.

So I think my father was driven to make me feel supported in that way. But he was also the equivalent of a stage mom, as far as sports. He was a sports dad. He was dead-set on making sure that everything I did was only to make me the best swimmer I could possibly be. My mom was more of the nurturing one. She went along with it, because you didn't argue with my dad. Also, she agreed with his reasoning, but not necessarily his methods. It was intense.

I figured out that in the 13-and-a-half years that I swam, I had a total of about two months off. That week, maybe two days here or there – there was not a lot of time outside of the pool.

MW: Were you under a lot of pressure?

JOHNSON: I didn't know, really, what I was missing till I was in college. Everyone else was talking about, ''We used to do this, go there.'' I never had time to get into trouble with the neighborhood kids. I never did sleepovers at a friend's house. My friendships were not that kind.

I realized after the fact that by having that kind of childhood, I did miss out on stuff. But, also, because of that childhood, there's a lot of discipline that I have. I think the reason why I can still get paid a few pennies here and there for the art that I do, still have the drive and passion for it, is because I have discipline. I don't give up on it. I don't just throw it by the wayside. There's sacrifice. I made sacrifices as a kid without knowing it, and there are sacrifices you make as an artist – if that's what you want to do.

MW: With sports, with the swimming, there are benchmarks. You win a trophy. You place in a meet. But art is a much different arena. What gratification do you get from performing that's similar to being ''statewide all-American'' or whatever?

JOHNSON: To be an artist, you have to be selfish to be selfless. The selfish side of me, I get to express myself in creative ways. I have an outlet to do that. And I have people who are interested, who will be there. I learn so much about myself by doing this. I love that, just learning about me as a person and why I'm here, why I choose the things that I do. The selfish part gets its say.

The selfless part is seeing people laugh, and enjoy themselves, and want to come back. To have an excitement that maybe they didn't come with. All the cliché things are actually very true and very real. To make a person laugh and then cry, or to be silent and sit and listen, it's a wonderful feeling to know that what you do can take someone else someplace in their own life. That's the selfless part of it. Art is about the experience that the observer has. If no one really cares about it, then your art's not really going to exist very much. [Laughs.]

MW: If there was no audience, I suspect you'd still be doing it.

JOHNSON: But that's not going to be fulfilling. Both parts need to be balanced.

MW: And that desire goes back to childhood. You got to college and something happened on that front. What?

JOHNSON: I was recruited by a bunch of different colleges. I was flown out to Georgia, to Indiana, to Iowa. My mother was like, ''Just go, they're paying for it. You might get there and like it.'' Of course the University of Hawaii calls me and my mom's like, ''No, you're not going there.''

So I was all set on the University of Georgia, because I really liked the swim team. I was going as a journalism major. But then I went to South Carolina thinking, ''I'm going to Georgia, but my mom's forcing me on this plane to South Carolina.'' As I got off the plane in Columbia, I saw a phonebook with something on it about celebrating the arts that year. It said right on it, ''More theaters per capita than New York City.'' That really caught my attention. So I left there agreeing on the University of South Carolina. They had a decent journalism school. They were in a city. And they had more theaters per capita than New York. [Laughs.]

It was terrible. It was horrible. I quit after my first year. I dropped the scholarship my parents wanted me to work all my life for. I hated it. It was everything I didn't want to be. I could take grueling – this was abusive. I did not like any of the swimmers. They were really nasty, disgusting people. The coach was a jerk. He was supposed to be the top-ranked American in his event for the 1980 Olympics, the ones we boycotted. He was a bitter, bitter guy. I hated it. It wasn't worth it. So that's where my swimming career came to an end.

That same year, I auditioned for a production of A Chorus Line. I'd never danced in my entire life. It was sponsored by the Columbia City Ballet and a well-established theater there. So there were all these best ballet people in the state of South Carolina, and me, some swimmer who likes to sing and dance and has aspirations of being a star. But I was cast as one of those ''God, I hope I get it'' people, and good-bye and you come back at the end. You sit out the rest of it.

It ended up that one of the people had to drop out, and the choreographer said to me, ''Look, we're going to put you in this part'' – a part that makes the final cut. ''You've got to come to every class you can come to at the ballet school – jazz, tap, modern, whatever – for free. But you've got to look like you can dance. I'll give you any time you need, but you've got to put the time into it.'' And I did, for five months, basically just working on Chorus Line choreography. That pretty much sold me from there on in.

I dropped journalism four weeks into my freshman year and became a theater major. [Laughs.] And I never graduated.

MW: How was the production?

JOHNSON: Chorus Line went great. It went great. I think that's when my dad figured out that this is a passion of mine. I think he recognized it, because closing night was one of the most major things in my life at that point.

I went back into this hard-to-get-to corner of the stage, maybe a half hour after the show had closed. People were hanging around. My parents were waiting for me. And I just kind of broke down crying. It was like, ''What am I going to do? I am going to miss this.'' You get the adrenaline. You get the focus. There's such an element of fulfillment – and then it's gone. Final applause, curtain down. I'm much better now, don't get as attached as I did when it was all new. But I broke down. ''Can't catch your breath'' type crying. And, all of a sudden, I look over and my father's just standing there looking at me. I tried to compose myself, and he just said, ''It's okay. It's okay.'' Which floored me. I think seeing me that emotional over something, that's when he got the picture.

From there on, I just started doing plays, acting in plays. One thing led to another and I had all these opportunities. I directed, I choreographed, I acted, I musically directed, I wrote.

MW: And you came to D.C. in 1997. Why here? The typical answer would be ''met a boy.''

JOHNSON: Well, I did meet a boy. But I also had family who lived on the outskirts. Also, D.C. was a great theater town, and it wasn't New York. By that time, I decided that I didn't want to be another actor in New York City. I knew I wouldn't be happy just being an actor.

I came to D.C. and just threw my résumé all around town and thought nothing of it. Studio 2ndStage called me in because they were looking for understudies for Hair, and they offered me a part of an understudy. I actually got to go on a couple times. Then Keith Alan Baker, the head of 2ndStage, offered me my first starring role. The next summer they did a show called Kerouac, which was about Jack Kerouac and Ginsburg and all of that. It was one that we all kind of wrote ourselves.

MW: And you played Kerouac?

JOHNSON: Yeah. From there, it just went. Joe Banno saw it and asked me to audition for Much Ado About Nothing at the Folger, and I got that. I got to know Chris Henley that way, so they asked me to come to Washington Shakespeare Company. That's how all of that started happening.

MW: In the context of you and D.C., how big a part is Ganymede Arts?

JOHNSON: Major.

MW: And Ganymede is no more?

JOHNSON: It's gone. It's history

MW: It was the only specifically LGBT theater company in this very gay town, right?

JOHNSON: Right. It was originally Actors' Theatre of Washington, founded in 1992. It was not a gay theater company. It was a theater company [for] actors and budding directors who weren't being given the opportunity to direct or act in certain roles. If they wanted to do a project, that's where they could do it.

In 2000, they were going to close it, because they didn't need it anymore. Jeffrey Keenan, who no longer lives here, said, ''Give it to me.'' He took over and changed it to be the gay and lesbian theater company. They just didn't have a lot of funding – well, like we ever had a lot of funding. By 2003, he was sick of it, trying to get people to support it. At the time, we were doing Naked Boys Singing that first time, and he had invited me to stage it. I guess he was impressed enough by the staging that – I was in Florida visiting my folks and my phone rang – and he said, ''In two weeks, at the end of June, I'm closing Actors' Theatre. I will give it to you if you want it, but other than that, I'm closing it.'' I was like, ''Yeah, give it to me!'' My dream was to run a theater company. That's how I got hold of it. That was 2003.

What we inherited was a company that had no books. There was no board. There was no staff. I took over $30,000 in debt. … What I saw as my beacon of hope was that it had a 2,000-person mailing list. If we were to start our own theater company, it could take us two years to get 2,000 people on a mailing list. ''We're fresh, we're new, and we have 2,000 people we can tell.'' That's what I was handed. We got out of debt, but we never made any money.

MW: Well, I guess you made $30,000.

JOHNSON: We made $30,000. Exactly. [Laughs.]

MW: And produced some popular shows.

JOHNSON: I'm proud of everything we did. Maybe outside of two or three reviews, we had a stellar critical record. Some of the best reviews I've read in the 14 years I've been in town were for Ganymede productions. I'm not saying that to pat my back. I'm proud of that. Ganymede did a lot of great things.

When I first took over, I was not a ''gay political person.'' In fact, to me, I always lived my life as far as being gay as it's just an aspect of who I am. I don't define myself by that. I can define myself as being gay just as easily as I can define myself as being a piano player or being Pisces.

MW: Did Ganymede get to a point that it was more limiting than liberating?

JOHNSON: No. Actually, Ganymede liberated me a little bit more. It made me understand why it was important to have a gay theater company – mostly because I had to make the argument for it a lot in the beginning.

MW: What is the argument?

JOHNSON: It was the only theater company fully dedicated to telling the gay life, whereas you look at any theater in town and it's a percentage. There's the gay play you've got to do. There's the black play you've got to do. There's the musical. The comedy. Maybe we can fit in a play about this racial group, or this religious group. The gay story is only part of the formula, not the formula.

MW: And it closed because you decided it was done?

JOHNSON: It was funding. But, ultimately, I believe it was support from the gay community. I think they came to see our stuff and appreciated it. I don't think they supported it. I don't mean that in a bitter way, just a matter of fact.

It was, I believe, the political mindset of D.C. They want to be able to say, ''We donate to Studio Theatre.'' ''We donate to the Kennedy Center.'' Who wants to say they donate to Ganymede Arts? The whole room would say, ''Who?''

We were always trying to just milk anybody we could for five cents towards getting the next play open. The board got to the point where they wouldn't even allow me to plan on having a play unless we had the funding already there. I was like, ''How can you raise funding for something that isn't happening?'' The board was trying to be very smart about it, because in the early days we were like, ''We're going to do this play. We're going to do it.'' It's the whole Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney – if they got the money or not, they're going to do a play. And cross their fingers that hopefully the ticket sales will pay for it. And that's how we were in our most successful years. Come hell or high water, this play is going to happen.

But after [board president] Noi [Chudnoff] died, and because the economy was tanking, the board got extremely cautious. And trying to get anybody to give money was really, really hard.

MW: I look at your creation of Galactica and the role of Little Edie, and wonder which is the jewel in Jeffrey Johnson's crown.

JOHNSON: I think people who see me and know me as Galactica only think of that. Little Edie. To me it's all acting. Some people consider me a drag queen. That's the farthest from what I think I am. I feel myself an actor. Just happens to be that either this character I created, or this character I'm doing, is a woman. But that doesn't make me a drag queen. I'm not belittling a drag queen. It's just not what I am.

MW: There's a phrase I read recently: ''gender sterilizing.'' You wrote it. What does it mean?

JOHNSON: It's sort of like with Galactica. One of the reasons I think I don't fit into ''drag queen'' is because I never try to pull off that I'm a female. I want people to keep seeing the guy. You hear the guy. I don't sing in some falsetto. I want the thing of Galactica being that once you recognize it's a guy, you get caught up in the whole artifice of the feminine qualities and the play on male-female roles. You get lost again. Yes, I have boobs, but Galactica is not a chesty woman. She has enough lump there to show that she might have a breast, but I still want people to see a male body. I don't wear drag-queen makeup. More than base, I just wear a little blush. I wear a little bit of eye-shadow, a false eyelash. I basically put on makeup as if I was a woman just going out walking.

With [Ganymede's production of] Les Liaisons [Dangereuses], for example, I wanted to do that play because as I read it, I thought, ''Let's do it all in drag.'' Then I thought, ''No, this doesn't need any camp.'' The humor of it is a black, dark, biting, wicked humor, and camp would totally destroy it. The funny thing is, some of the female characters in this play have much more masculine qualities. The male characters, some of them, have much more feminine qualities. So, how interesting would it be if we ''gender-sterilized'' the play, and had all men just to create a blank slate? The closest we could get to genderless was just to have one gender. But not do it in drag. Do it still in men's clothing. Play women, but still present yourself as a man. The one womanly thing I had was a headband.

The audience could take it so many different ways. They could take it at face value. They could say, ''This is a comment on gay society today.'' I wanted people to see their own story, however they wanted to interpret what that meant.

MW: Edie Beale was definitely a woman, and your performance of her has been acclaimed. When can fans see her again?

JOHNSON: I don't know. To be honest, she surprised me when she showed up in December. After I did the little tour the year before, I said, ''Okay, I'm putting her away for a little while. Then, in November, I thought, ''Why not?'' A night or two of Little Edie, just to see if the interest is still out there. And it sold out.

MW: Galactica, meanwhile, is on deck. You've got this new, ongoing Black Fox happy hour lined up. What can we expect?

JOHNSON: It's a jazz club, so the music I'm going to focus on is a cross between cabaret with more of a jazz flavor. The two musicians I've got, I haven't worked with them before, but we've been rehearsing. Both of them are very prominent musicians in the jazz community. There's the bassist, Ethan Foote. He's amazing. And Aaron Myers is keyboards. Aaron actually plays the second show on first and third Fridays at Black Fox. And he's amazing.

Audiences are going to have so much fun. It's unique. There's nothing like it. They can have great food, awesome drinks and wonderful entertainment, surprises and laughs – and let it all hang out with the ''pink-haired one.''

Special Agent Galactica's Black Fox Happy Hour begins Friday, March 23, running the second and fourth Friday monthly, 6 to 9 p.m. No cover. 1723 Connecticut Ave. NW. For more information, call 202-483-1723 or visit pinkhairedone.com.

...more